Every now and then, some new information comes along that just blows away everything that I was taught about training. Even more rare is the when older research gets updated and repackaged in a way that surprises me in startling new ways. Both happened to me last when I dug deeper into the research around something called “polarized training.” It may fundamentally change the way that I train– and you may want to try it as well.

Every now and then, some new information comes along that just blows away everything that I was taught about training. Even more rare is the when older research gets updated and repackaged in a way that surprises me in startling new ways. Both happened to me last when I dug deeper into the research around something called “polarized training.” It may fundamentally change the way that I train– and you may want to try it as well.

Polarized training has also got to be one of the most misunderstood training principles. I’ve heard multiple coaches denounce it by describing training strategies that “focus entirely on high-intensity intervals” or “fat burning training plans that involve hardly any speed work.” Yet when I scratched beneath the surface, they were both talking about polarized training– but only focusing on one aspect of it. As I describe below, I confess that I was also very confused about it when I first encountered it ten years ago. Once you get past all the confusion, there are some very serious reasons to care about polarized training because it’s been around for awhile and it’s here to stay.

What is Polarized Training?

Polarized training revolves around a few key principles:

- Long and Very, Very Slow. About 80% of your training should be really slow and easy. If you are a follower of the Coggan five-zone system, this means zone 1 and the very bottom (maybe 5-10%) of zone 2. If you are a use heart rate, it’s about 70% of max HR or below. It’s easy. Really, really, really easy.

- Almost No Threshold Training. This is the biggest surprise for me. Threshold pace is very close to what we race at, regardless of whether we’re running a 5K or a half-marathon. Polarized training models have almost none of it– not even as the race season draws closer. This just seems to violate the training principle of specificity in the biggest way.

- Fast is Very, Very Fast. About one out of every five training sessions is devoted to interval training. These interval sessions are very fast– about 90% of maxVO2 or higher. For running, these are just a little slower than all-out mile pace. For cycling, these are all-out two- or three-mile sprints. Ouch!

- No Major Periodization. There are slight variations in the program between pre-season and race season, but they aren’t huge. Unlike traditional block periodization, the changes are more fine-tuning than massive changes.

Why Should I Care?

If you’ve read this far, polarized training may seem like the craziest training idea yet. It sounds like high-intensity cross-fit meets 1970’s long-slow distance (LSD) training. It’s no wonder that coaches latch on to just one aspect of it and denounce it. Yet there are some very good reasons why it makes sense and why you should care about it.

Most World-Class Athlete Already Do It (Even If They Don’t Know It). I first heard about polarized training when I was reading an article titled, The Search for the Perfect Intensity Distribution in the December 2004 issue of Running Research News. I talked about– but apparently misunderstood– this article in an earlier post on training periodization. The article described the findings of a researcher named Stephen Seiler. Examining the actual training logs of world- and national-class cross-country skiers, he noticed that they followed the polarized training model. At the time that I read this, I didn’t really understand the profundity of his finding. I just thought it was a different way to do your base miles in the pre-season; instead, Stephen found that polarized training was a quality that pervades all phases of training. Fast forward 10 years and the whole academic research community has found the same pattern over and over again– world and national class runners, cyclists, rowers, and cross-country skiers all followed the same polarized training model. The same pattern also covers just about every endurance distance. For instance, the pattern shows up from national and world-class 5K runners up to marathon runners. Mr. Seiler admits that this finding surprised him because he was always led to believe in the training model that emphasized specificity and lots of threshold training– both of which were absent in polarized training. Stephen Seiler has a down-to-earth, humble (almost self-deprecating) tone, which makes it much easier to accept his findings and agree that there might be something to it. If you have 30 minute to kill, be sure to watch an excellent presentation he gave last year in Paris. Or if you prefer to take in shocking news by reading about it, you can read a chapter that he recently wrote covering the same material.

Most World-Class Athlete Already Do It (Even If They Don’t Know It). I first heard about polarized training when I was reading an article titled, The Search for the Perfect Intensity Distribution in the December 2004 issue of Running Research News. I talked about– but apparently misunderstood– this article in an earlier post on training periodization. The article described the findings of a researcher named Stephen Seiler. Examining the actual training logs of world- and national-class cross-country skiers, he noticed that they followed the polarized training model. At the time that I read this, I didn’t really understand the profundity of his finding. I just thought it was a different way to do your base miles in the pre-season; instead, Stephen found that polarized training was a quality that pervades all phases of training. Fast forward 10 years and the whole academic research community has found the same pattern over and over again– world and national class runners, cyclists, rowers, and cross-country skiers all followed the same polarized training model. The same pattern also covers just about every endurance distance. For instance, the pattern shows up from national and world-class 5K runners up to marathon runners. Mr. Seiler admits that this finding surprised him because he was always led to believe in the training model that emphasized specificity and lots of threshold training– both of which were absent in polarized training. Stephen Seiler has a down-to-earth, humble (almost self-deprecating) tone, which makes it much easier to accept his findings and agree that there might be something to it. If you have 30 minute to kill, be sure to watch an excellent presentation he gave last year in Paris. Or if you prefer to take in shocking news by reading about it, you can read a chapter that he recently wrote covering the same material.

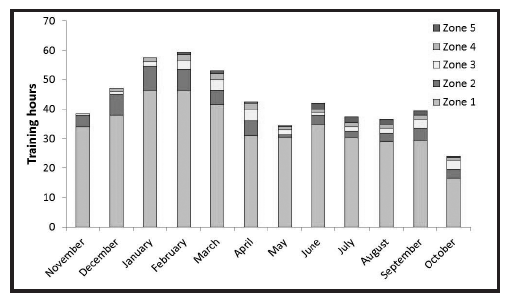

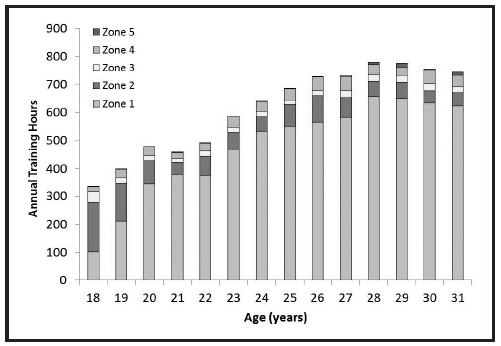

- Slow Means Really Slow. When it comes to the easy stuff that comprises 80% of the training that most world-class athletes do, Mr. Seiler observed that this training fell in the range below the ventilatory threshold (VT1). This is the highly-subjective point where breathing becomes harder in a non-linear fashion. Basically, if you can’t hold a normal conversation and can’t exercise perfectly comfortably with your mouth closed, you’re above VT1. This follows a three-zone system often used by exercise physiologists, with zone 1 being below VT1, zone 2 being between VT1 and lactate threshold, and zone 3 being above lactate threshold (if you want more precision, here is a video describing VT1 and the three zone model). Most of us, however, don’t use a 3-zone training model; instead, we tend to use a five-zone model similar to the Coggan power zones, in which (a) zones 1-2 (five-zone model) correspond to zone 1 (three-zone model), (b) zone 3 (five-model model) corresponds to zone 2 (three-zone model), and (c) zone 4-5 (five-zone model) corresponds to zone 3 (three-zone model). Mr. Seiler concluded that 80% of training fell with zones 1-2 (five-zone model). However, this doesn’t really tell the whole story. In fact, for elite athletes the vast majority of that easy 80% was zone 1 (not zone 2) within the five-zone model. This means workouts below 70% maxHR– a range that most of us probably would consider way too easy. Yes, the Ryan Halls and Meb Keflezighis of the world were spending most of their time running “super slow” in zone 1 (note, however, that “super slow” for them may still be a 6:00 or 7:00 pace)! The following graph, for instance, shows how much time the great Ingrid Kristiansen spent in each zone during the year before she set the world records for both the 5K and 10K! This is really incredible because I’ve always been told that zone 1 (five-zone model) didn’t have much training value other than recovery. And just in case you think that Ingrid Kristiansen’s data was an abnormality, below it is the 14-year training data of Bente Skari, a female cross-country skier who won an olympic gold medal, five world championships, and an astonishing 46 world cup victories. Both athletes spent almost all of their training time in zone 1 (granted, Ingrid Kristiansen did more threshold work than maxVO2 work between February and April, but all of her harder work was absolutely dwarfed by the time she spent in zone 1)

- It Makes Sense for World-Class Athletes. At the world-class level, this kind of training actually makes a lot of sense when you think about it. At the very tip of the field, world-class endurance athletes are so fit that their lactate threshold (LT) is as close to their maxVO2 as it’s going to get. The only way to get it higher is to push the velocity while at maxVO2 (vVO2max) higher. As I think Philip Skiba would describe it, they need to raise the roof of their house to accommodate a higher ceiling. Running intervals at close to vVO2max intensity, however, is extremely taxing– and that means a lot more recovery is needed. Hence the high-volume work has to be at a much lower intensity. Voilà, the training just naturally gets more polarized!

- Includes Early and Later Training Phases. As I noted above, this is the part of the polarized training that floored me. Looking back at Ingrid Kristiansen’s one-year training graph, somewhere in the middle of all that polarized training and massive time in zone 1, she set two world records. That’s right– the training stays polarized right up through race day! At about 6:49 in the video presentation above, Stephen Seiler talks about Veronique Billat’s findings when she reviewed training logs from the French and Portugese national teams in the last 3 months before the Sydney Olympic marathon trials. Mind you, this is the final, most specific phase of training when you would expect that athletes would be trying to fine-tune their bodies to handle the precise pacing of the big race. Instead, Ms. Billat found that these exceptional runners (one a 2:06 marathoner) became even more polarized as the trials drew closer– they were running more easily in their long runs and harder (up to their 3K race paces) during their interval sessions! At the same time, they were spending even less time at lactate threshold. So much for specificity and so much for my ideas about funnel periodization.

- Polarized Training Isn’t Created in a Lab– It Reflects Real-World Training. In general, exercise physiologists make lousy coaches. There are two inherent problems with most exercise physiology studies. First, they try to isolate one variable (e.g. one nutrient, one training factor, etc) and see if the presence or absence of that one variable improves or harms performance. By contrast, coaches work in the real world and know that everything is tied together as a seamless whole. Second, exercise physiologists tend to perform short-term studies (e.g. 12 weeks is commonly the longest length of time most studies take place). This reflects practical limitations– most people don’t want to be a lab guinea pig for long periods of time. These are called intervention studies because they take an exercise subject and try to do something new to them. By contrast, almost almost all of the studies backing up polarized training have started with descriptive studies— looking at what people do in the real world and trying to identify patterns of what’s worked and what hasn’t worked. One of the problems with descriptive studies, however, is that their reliability depends on how things are described. For instance, how do we decide if a training session is really a zone 1 “recovery effort”? For instance, do we look at the average speed attained during the effort, do we look at a minute-by-minute report of running speed and parse the run into different minutes in each training zone, do we look at heart rate during the run? What is impressive to me is that different exercise physiologists have parsed the workouts of athletes in a host of different ways (I won’t bore you with the excruciating details) and the consistent observation is that training is consistently polarized among world-class endurance athletes. In fact, I don’t know of a single recent research study suggesting that training patterns weren’t polarized among top-level athletes.

- The Studies Exclude Individual Variations. “That’s all well and good,” you might be saying, “but that’s only for some people. Certainly there must be a ton of exceptions. Plus I’m not a world-class athlete.” In the video (at about 24:30), Seiler talks about a very disciplined crossover study showing the superiority of polarized training over traditional lactate threshold training. This study used very good (but not exceptional) athletes and had each athlete perform 6 weeks of lactate threshold training and 6 weeks of polarized training (the group was split in half with one group starting with lactate threshold training and the other group starting with polarized training). Testing each group showed a clear pattern. Almost without exception, athletes did better after polarized training on almost every performance indicator and worse when they used more traditional training plans. Granted, both this study and the next one involving everyday athletes are intervention studies– and are subject to all the follies of an exercise physiology study. For instance, in determining that polarized training was better than threshold training, what kind of threshold training did they use? After all, anyone can concoct a threshold training plan that is guaranteed to fail.

- It Works Better for Age-Group and Everyday Athletes. If you read what I wrote above about why polarized training might make some sense for world-class athletes, you may be thinking that polarized training shouldn’t work so well outside of this narrow band of elite superstars. After all, most of us have a pretty sizable gap between our lactate threshold and our vVO2max, so we should be better off working on LT to narrow the gap, right? As logical as that sounds, it doesn’t work that way. The study I just mentioned in the last bullet point involved pretty strong cyclists, but certainly not at the world-class level. If that weren’t enough, there is another recent study involving purely recreational 10-K runners that showed the superiority of polarized training. This study requires a little bit of explanation, which Mr. Seiler is happy to provide starting at about 27:10 in the video above. The takeaway from Stephen’s explanation is that, if you really want to realize the benefits of a polarized training plan, you really have to follow it closely– you have to keep all of your slow running very slow and your intervals fast. No junk miles! If you try to speed up your slow runs, you only end up slowing your race times!

- Polarized Training Doesn’t Require Insane Volume. One of my friends commonly criticizes polarized training claiming that it requires working athletes to spend an impractically large amount of time doing easy long workouts. This doesn’t turn out to be true. In the study on recreational athletes just mentioned, for instance, the runners assigned to each group ran roughly 30-40 miles per week and the overall stress of the two groups (using a so-called TRIMP scoring) was approximately the same. In addition, referring back to the table showing Ingrid Kristiansen’s training schedule, she was running about 40-60 hours a month. As world class runners usually don’t take a day off, that comes out to about 1-1/3 to 2 hours a day– pretty darn reasonable for someone who is about to set two world records in that year. Polarized training doesn’t require training more– it just requires being smarter and more focused on the purpose and specific pace of each workout.

-

It Works Really Well with Older Athletes. In recent posts, I talked about how world-class old guys stay in shape. I also reblogged a great post from Canute’s Efficient Running Site about how to adapt some of these ideas to training. Ed Whitlock is probably the greatest older marathoner and was the first man to break 3:00 (twice!) at 70 years of age or older. As noted in Canute’s post, it just so happens that Ed Whitlock has always used polarized training. The two photos on the right are almost a visualization of polarized training. The top photo shows Mr. Whitlock on one of his daily 2-3 hour runs (yes, he favors lots of volume). He really is shuffling along at a pace that most of us would consider easy. The bottom photo shows him during one of his races where is running well under 7:00 pace (a 3:00 marathon requires a 6:52 pace). For Mr. Whitlock, it appears that he stumbled upon polarized training accidentally– just following what made sense to his body. In his earlier years, he had much less success following a traditional training plan of higher intensity and speed work. After transitioning to a polarized model in his 60’s, his performance dramatically improved compared to his age group peers.

It Works Really Well with Older Athletes. In recent posts, I talked about how world-class old guys stay in shape. I also reblogged a great post from Canute’s Efficient Running Site about how to adapt some of these ideas to training. Ed Whitlock is probably the greatest older marathoner and was the first man to break 3:00 (twice!) at 70 years of age or older. As noted in Canute’s post, it just so happens that Ed Whitlock has always used polarized training. The two photos on the right are almost a visualization of polarized training. The top photo shows Mr. Whitlock on one of his daily 2-3 hour runs (yes, he favors lots of volume). He really is shuffling along at a pace that most of us would consider easy. The bottom photo shows him during one of his races where is running well under 7:00 pace (a 3:00 marathon requires a 6:52 pace). For Mr. Whitlock, it appears that he stumbled upon polarized training accidentally– just following what made sense to his body. In his earlier years, he had much less success following a traditional training plan of higher intensity and speed work. After transitioning to a polarized model in his 60’s, his performance dramatically improved compared to his age group peers.  And, from reviewing the list of runners in my previous post, it appears that Mr. Whitlock is not alone. Granted, runners in their 60’s and 70’s can’t absorb quite the same level of speed work; except for the slight reduction in volume of speed work, however, they tend to follow classic polarized training year-round. Ed Whitlock has found success by daily long runs through a cemetery near his house and a weekly speed session or 5-K race.

And, from reviewing the list of runners in my previous post, it appears that Mr. Whitlock is not alone. Granted, runners in their 60’s and 70’s can’t absorb quite the same level of speed work; except for the slight reduction in volume of speed work, however, they tend to follow classic polarized training year-round. Ed Whitlock has found success by daily long runs through a cemetery near his house and a weekly speed session or 5-K race.

My Experience This Summer

If you’ve been following some of my training “aha” moments over the last few weeks, you may have noticed the same pattern that I did. Not that long after my 40-K TT, I wrote about the role of MCT-1 in lactate clearance. This led me to experiment with some blend workouts with my team and even incorporate high-intensity into some nasty hill workouts. But I noticed something very strange going on with all this hard running: my cycling lactate threshold performance was improving!! At the time, I thought that all of this high-intensity interval work was simply patching a major MCT-1 weakness and I questioned whether it was a good idea because doing such maxVO2 efforts was very unspecific. Nevertheless, one measure very specific to my race performance (i.e. my 30-minute TT power) was showing huge improvements.

My experiments this summer violated the training principles that I outlined earlier. But the results are perfectly in line with what polarized training has been suggesting they would be. At the same time, as I look back over my training diary, my training runs have have been extremely slow, as I mentioned in a post from several weeks ago. Maybe I was stumbling onto some of the same ideas that Ed Whitlock had encountered?

Easier Easy Days and Harder Hard Days

Polarized training isn’t terribly different from the way that most of us already work out. The difference is that the easy days are easier and the hard days are harder. It’s the stuff in the middle– all the “sweetspot” and “tempo” work– that goes on a serious diet.

Last year, my training for Powerman Zofingen was probably the poster child of what polarized training should not be like. Starting in February, I was working super-hard on the bike. By April, I was taking long 80 mile rides on the weekend, trying to keep every bit of the ride between 85-92% FTP. Even my easy rides were spent at 85% FTP. My runs were no less merciful as I was putting in long tempo efforts at least twice a week. Not only did I end up with an injury that took me out three days before the race in September, but I also was getting slower. I was beginning to really struggle on my tempo runs; my team mates at the track (for the few times that I went) were creeping up on me a lot faster. But the worst part of this kind of training: I was miserable. I dreaded riding my bike. I hated anything to do with running. When I would get home from my long rides or runs, I would curl up in a fetal position on the couch and my wife and our cats knew that it was unsafe to ask me anything. After Zofingen, it took me a good three months to get back to my former self… and I did that with a bunch of 800s and mile repeats with plenty of recovery.

If I tried a polarized training plan, my volume would likely increase from where it is now. That’s only because it’s the end of my season and I’m tired– I’ve earned some low volume weeks. But I certainly don’t have to raise my volume to the level that I was at before Zofingen. Best of all– it would be easy volume. I think this is the key factor for keeping me happy. And, should I decide to try PMZ again, this is clearly the way to do it.

Now Is a Perfect Time to Test it Out

Obviously, you don’t want to start a polarized training plan if you’re about to start race season or are in the middle of it. Here in Seattle, our summer race season is coming to a close and, because I don’t race cyclocross, my off-season is right around the corner. Now would be a great time to test out polarized training for a couple of months because I can always return to a more traditional plan later on. Furthermore, the high-volume of a polarized plan fits in very well as the base months for either a Lydiard training plan or a funnel periodization plan, so how could I lose? Starting now and working through February or March will give polarized training a great test run in the most harmless way possible.

- Ramp Up to 12-18 Training Hours per Week. Over the coming months, I will try to ramp up to 2-3 training hours per day. I’m thinking 6 days a week of running and 6 days a week of cycling, following a schedule roughly like the one outlined below. Ramping up the running should be fairly safe and easy to do because the pace/effort has to be so darn low. One way to easily ramp up would be to take a “reverse Galloway” approach and start by walking easily– then tossing in longer and longer “running breaks” until I was just running continuously. Then it might not be a horrible idea to add a very short (10-12 second maximum) sprint over 20 minutes or so on my easy runs and rides.

Monday: Easy 60-90 minute bike (AM); easy 60-90 minute run (PM)

Tuesday: Running intervals (PM)

Wednesday: Easy 60-90 minute bike (AM); easy 60-90 minute run (PM)

Thursday: Bike intervals (PM)

Friday: Easy 60-90 minute bike (AM); easy 60-90 minute run (PM)

Saturday: Race or long 2-3 hour brick workout (half running; half cycling)

Sunday: Long 120-180 minute run or 180-240 minute bike (alternate weekends)

- 6-8 Minute Interval Sets Plus 1-Minute Sprints. Stephen Seiler did a little more research into the ideal intensity that one should be doing on a polarized training program. He found that 4×8-minute intervals were profoundly better than longer or shorter intervals. He discusses this point at about 29:30 into the video linked above. Also, Runner’s World posted a quick summary of his findings or you can just download the full paper from ResearchGate. Starting at 6:00 intervals and shortening recovery times will give me more options to play with over the coming months. I also want to add in a bunch of 1-minute lactate clearance sprints at the end of the workout. The research has shown that MCT-1 doesn’t increase much with polarized training– and I sadly need a lot more of it.

Of course, I’ll let you know how it goes!

Thanks for reading and be sure to like the Athletic Time Machine Facebook page and follow us on Twitter @AthTimeMachine. If you found this post useful, please reblog it on WordPress, share it on Facebook, or retweet it on Twitter to share it with your friends.

Reblogged this on hanlinsblog.

LikeLike

Great information!

I have a question. Most training should be zone 1 which has a %HR of below 68%. What’s the lowest HR that counts as training? Training just a few beats above resting HR just seems too low.

LikeLike

Sorry about the delay getting back– took a long break from blogging. Your question is a good one and I really don’t have a good answer. I’m not a huge fan of basing exercise on heart rate though as (1) it tends to lag (i.e. heart rate responds slowly to changes in power or speed) and (2) it’s affected by too many external factors (e.g. heat).

LikeLiked by 1 person